|

THE HISTORY OF

MARINER KAYAKS: |

| Design development:

the How, Why, Who and What For |

| We began designing

kayaks in 1980 out of a desire to have the best equipment possible and a dissatisfaction

with what was then available to us. There have been ten Mariner designs in production.

Why? Mostly because we’re crazy about kayaks. Sort of like a set of golf clubs, we

want a boat for every type of paddling we might feel like doing. Each of our kayaks is a

different blend of design features to emphasize certain qualities for best performance in

differing applications. |

| A proper fit to

paddler and purpose is of great importance in developing a good working relationship with

your kayak. To fit smaller or larger kayakers some builders offer what is basically the

same design in different lengths, while others offer what actually is the same design in

different heights, by simply cutting down the hull’s freeboard before joining the

deck. That’s the easy way but not necessarily the best way! Smaller paddlers usually

need a boat that is smaller in all dimensions, not just with a shorter hull or lower deck.

Just the opposite is needed for bigger paddlers. In contrast, each of our designs is a

distinct individual, to best suit distinctly individual paddlers. What follows is a little

history and guidance as to who and for what purposes each of our designs is best for: |

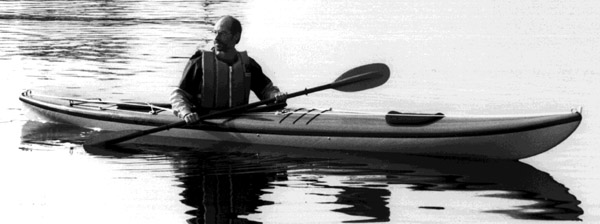

| Mariner |

Cam touring in the original

Mariner |

| The sea kayaks we

first owned and the others we tested in our search for better kayaks had left us

frustrated by their poor handling in winds and waves. In 1980 we brainstormed several

unique solutions to the problems of pearling and broaching in following seas, weather

cocking in sidewinds, and slamming and plunging in head seas. Although we were at first

looking for ways we could modify the boats we owned at the time, it became clear that many

of the solutions could not simply be added on, but would require a completely new design

to incorporate the features we had come up with to improve on a sea kayaks handling. Once

we decided to try building our own kayak we spent months researching the subjects relevant

to kayak hull design. One offshoot of this research is the resistance prediction method

Matt developed for Sea Kayaker magazine's kayak tests. We worked out a design we felt

would solve the handling problems and also get the largest gear capacity for the least

paddling resistance. Cam built some model kayaks that helped visualize the shape. One of

the books we found had a fairly simple way of constructing a full size version of the

design Cam eventually drew. (Actually Cam redrew the hull plan several times and Matt

redid the mathematical calculations each time in order to get the prismatic coefficient

that we had concluded was best for a fast cruising kayak.) |

| We decided we should

test our design extensively before putting too much work into it. Using our modifications

to Alan Byde’s plug making technique we built a rough plug and waterproofed it for

paddling. We began testing, and modifying, retesting and modifying, and retesting etc.

etc. This continued until, extremely pleased with the results, we were confident enough in

the kayak’s design to start the several months of unpaid labor it took to fair and

smooth that first plug to our perfectionist standards. Nine months after beginning we were

the proud parents of the first Mariner. |

| The original Mariner

not only performed beyond what we had been hoping for but was an immediate success with

other paddlers as well. Several of the earliest testers were expert paddlers who, out of

frustration with what was available, had also designed and built their own kayaks. They

told us the Mariner had the performance and handling that they had not been able to find

in the marketplace and had been trying (with less success) to build for themselves. Though

it had not been our original intent to become kayak manufacturers, all we were after was

the best kayak to paddle, one thing does lead to another and we soon found ourselves in

business. |

| Not only had our

original design ideas worked well in solving the problems we had tackled but in many ways

we had been remarkably lucky. The original Mariner had some excellent handling

characteristics that we hadn't exactly planned. Crisp carved turns, dynamic stability in

waves, and an unexcelled ability to catch and ride even small waves. Needless to say we

began figuring out just why the Mariner handled so much better than any kayak we had

previously paddled, both out of sheer curiosity and so we could repeat its success with

future designs. |

| The original Mariner

won all six kayak races it was entered in during 1981. While there have been a few faster

kayaks (in a sprint) built since, the Mariner is still sought after by some sea kayak

racers for use when sea conditions are expected to be gnarly or the race is especially

long. For instance: in 1993 Steve Reifenstuhl won the second Iditayak kayak race, a

grueling 110 miles from Pelican Alaska to Juneau through challenging waters. His time of

20 hours 26 minutes was 3 hours and 59 minutes ahead of the next finishers (a double). The

next single (an Arluk) was 4 hours 43 minutes behind. At the half way point (the previous

years finish) he was over an hour better than the previous year’s much ballyhooed

fastest single (a skinny skin on frame kayak). His kayak was an original Mariner he

had purchased new back in 1982. (The first woman finisher used a Mariner II we

delivered just a few weeks before the race.) |

| We know of only four

paddlers (in three parties) who have paddled the entire exposed outer coastline between

Seattle and Glacier Bay, Alaska. In 1997 one of them used an original Mariner that we had

built way back in 1983. This doesn’t surprise us because all Mariners are built to

last a lifetime. In fact this particular Mariner had already seen many years of hard use

and surf landings on the open coast, including an early solo paddle circumnavigating

Moresby Island (in the Queen Charlotte Islands) by its previous owner. The

Charlotte’s exposed West coast is reported to be the highest energy (biggest waves)

coastline in the world. (We are happy to report that this "outside passage"

paddler’s partner and both of the other "outside passage" paddlers used

Mariner II’s. And even happier to report that Mariner kayaks were these

paddlers’ own first choice for their trip--we do not sponsor any expeditions.

It’s also worth noting that none of these paddlers, including the racers mentioned

earlier, used a rudder). |

| There is nothing

else that can move so much gear along with so little effort as the original Mariner. Many

times we’ve been thanked by larger sized expert paddlers who, until the introduction

of the Mariner with its roomy cockpit area, simply could not use any of the narrow sporty

touring kayaks previously available. It didn't hurt our sales that Cam's artistic talents

had made the Mariner visually beautiful. The lines were so attractive that often we had to

talk smaller paddlers out of buying one even though they had their heart set on it and

checkbook in hand. At 18" 5" long it would not be a suitable kayak for them

(especially when empty in a strong wind). |

| The Mariner was a

specialized sea kayak best suited to large experts. In order to quit turning away

potential customers we knew we needed another design that would get as much Mariner

performance and handling as possible into a more general purpose sea kayak. |

| Escape |

Matt in the Escape |

| The classic

Escape, a kayak with lots of gear volume and plenty of stability, has a unique hull shape

which gives it the ‘feel’ and sportiness of a smaller boat. Touring kayakers

were pleased to find that a big, stable boat did not necessarily have to handle like a

barge. Its blending of so many desirable qualities in a single design made the Escape a

runaway success, and inspired a host of kayak designers to attempt the same. A number of

kayaks from our competitors owe much (in some cases very much) to this boat. |

| One of these future

kayak designers took seven of his campmate’s kayaks out, one at a time, as far as he

dared into progressively rougher seas. He said he went out much further and felt more

comfortable in the Escape than all the others. (Significantly, our smaller third

design, the Sprite, was the kayak he found next most comfortable). When Matt first saw

this paddler’s later design on the top of a car, he at first thought it was an

Escape. |

| The Escape handled

so much better than what else was available in 1982 that at one point we were back-ordered

more than six months. Paddlers ranging from 250 pound men to 100 pound women are still

paddling Escapes they bought over 16 years ago. While there are now many more suitable

kayaks for small paddlers (including several of our own) the Escape was the easiest

paddling best handling kayak they could find back then and some of these small paddlers

are still so hooked on the gear capacity they haven’t wanted to give it up for a more

suitable kayak. |

| Our next several

designs took away most of the market for the Escape (except for larger paddlers with

bigger feet--up to size 14). If you are a larger paddler and you can find one used it

could still be a great choice. We have retired the molds but they are still serviceable

should you discover (by paddling a friend’s Escape or using our demo) that

you’ve found true love and it is the only kayak for you. |

| Sprite |

| We have always sold

kayaks by encouraging head to head demos with the competition’s kayaks. In 1982 we

would send our demo models off with a potential customer and suggest they go to the nearby

Montlake Cut section of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. There all the weekend boat traffic

funnels through creating a vicious and unpredictable cross chop as the numerous boat wakes

would rebound back into the channel from the near vertical walls. We’d suggest they

paddle into the Cut as far as they felt comfortable and then paddle about 1/4 mile away to

a nearby kayak shop and rental operation and do the same thing with some competing

designs. If a potential customer did these tests we almost always won the sale. Always,

that is, until Eddyline began marketing their new Sandpiper (the original

16' model not the 12' one with the same name they market now) as a kayak designed especially

for women. By the time the second woman told us that although they preferred the

Escape’s handling, the Sandpiper fit their smaller size better so they were going to

buy it, we had already heard enough. No way were we going to have a paddler try out kayaks

head to head with ours and then choose the competition. Cam got out his drawing board and

began designing a kayak for smaller paddlers. |

| The Sprite

wasn’t just smaller in fit, it also had many other features a smaller paddler needs:

1) Less windage and quicker turning so a smaller less muscular paddler could deal with

higher winds. 2) A smaller footprint on the water so the smaller paddler would have less

friction to overcome. 3) The ability to easily lean it for better control. 4) A cockpit

that fit a smaller paddler. |

| The Sprite also

appealed to those who came to sea kayaking from whitewater boats. They liked its ability

to track well while retaining a lively responsiveness to paddle strokes. They also liked

the cockpit fit that allowed them "body english" control of the Sprite that was

reminiscent of their whitewater kayaks. The Sprite also had an especially soft ride into

head seas. Cam (six feet and 165 lb.) liked the sportiness of this boat so much he was

happy to accept the slight loss of gear capacity and used it as his exclusive touring boat

for the next two seasons. |

| The Sprite had lots

of advantages for smaller paddlers. Although it wasn’t designed particularly for top

speed it moved along smartly. Several woman did very well using the Sprite in our local

sea kayak races. When one kayak outfitter decided to sell the Sprite they had been renting

to the public for the previous four years (twice as long as with most of their rental

kayaks--Mariners just hold up to hard use better) they discovered they had a problem.

Three of their own kayak instructors all wanted to buy it and the politics got a little ugly. |

| Mariner XL |

| The late Harry

Roberts was associated with Sawyer Canoes back in the 1980’s (V.P. if we remember

correctly). Harry called us out of the blue one day in the Spring of 1984. He wanted

Sawyer to build the sea kayak he had been hearing such great reports on. We told him we

already had a builder with exclusive building rights to the Escape (at least West of the

Mississippi). He wasn’t satisfied with just the East coast market so we revealed we

had since developed some other design ideas and thought we could produce a superior

general purpose sea kayak that would appeal to a wide range of paddlers in the middle of

the market (the market Sawyer wanted to aim at with their first sea kayak). Harry

indicated a firm commitment and wanted us to start immediately. We were to build them a

rough plug of the design. They would smooth the plug to their standards and build the

mold. They would build and market the kayaks and we would get a royalty on each one. |

| Cam went to his

drawing board and began putting our conceptions on paper. The building plans were a

refinement of the method he had developed for producing the Sprite. Rather than draw the

sections to the projected form of the outside skin as he had with the Mariner and Escape,

Cam drew only the essential lines--keel, chine, sheerline, deck shoulder and peak, making

allowances for the volume changes that would come with the next step. He then built the

plugs as strict chine kayaks to be planked with inch thick urethane foam and shaped in

much the same manner a surfboard builder carves a board from a blank. Where the Sprite

plug had been planked with only foam and then glassed on the inside, the frame of the XL

was skinned with plywood panels first to provide a more solid base for the foam and to

allow us to start paddling the plug at an earlier stage, and possibly make it a wood kit

boat as well. |

| Somewhere along the

line the deal with Sawyer fell through. Apparently Harry had been really enthusiastic

about the project, but the president of the company had gotten cold feet and decided to

stick to the area they knew best, canoes. It would have been nice if somebody had called

and told us this instead of our hearing it through the grapevine after we had put in most

of the work, but in the end it was Sawyer's loss and our gain. We finished the plug

ourselves in 1985 and considering the success the XL has had since we are glad it worked

out that way. |

| ‘Hot

Rod’ is how Sea Kayaker magazine’s group of independent test

paddlers described the XL in their review in the Spring 1987 issue. Click on XL reviewer's comments here or on "MARINER

XL" the "Reviews:" pickbox on the sidebar for the full review from the

start. They were impressed by its high secondary stability and minimum paddling effort at

cruising speeds, as well as its ability to handle following seas, surf and other difficult

conditions. In fact their head kayak tester liked it so much he didn’t want to give

it back, and finally ended up buying the one we supplied for their tests. (Last we heard,

over ten years later, he was still paddling his XL.) |

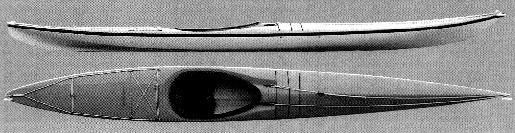

| With the

Escape Matt had developed a unique ‘runner’ along the hull’s mid and after

sections which improved tracking when level without slowing leaned turns. He modified this

‘runner’ concept in the XL to increase broaching resistance and to give it

better wear characteristics when compared with a ‘V’ keel. (See photo of the

hull in Mariner

XL). You’ll greatly appreciate this ‘runner’

when moving a heavy load through difficult water. The XL (and its very similar successor,

the Max) are the easiest kayaks you’ll ever use when it comes to keeping a downwind

course in steep following seas. The rockered ends, trim adjusting sliding seat unit, and

comfortable (secondary) stability when heeled onto its chines allow the XL to be turned

smartly. The long fine bow parts the water so gently and evenly that a bow wave is hardly

noticeable. (See photo in above link.) |

| To provide a good fit

for a broad range of paddler sizes, the XL foredeck at the cockpit is of medium height and

has deep kneebrace moldings extending forward from the cockpit. This allows a solid grip

at all positions of the sliding seat. Its combination of a low resistance hull with secure

stability and lots of cargo capacity make the XL an excellent all-around kayak for

activities from long distance touring to fishing and general knocking about. |

| If you've read the

kayak tests in Sea Kayaker's Winter 1993 issue you may have noticed the mention that the

Mariner XL's towing tank results had the ‘poorest’ fit (of the six kayaks

tested) with the predictions of their then new statistical model of kayak resistance. What

was not explained was that the XL had 7.5% less resistance at three knots and was 10%

easier through the water at four knots during actual towing tank tests than their later

simplistic model predicted. The ‘poor’ fit was because of the Mariner XL's

superior performance. At four knots (a good cruising speed) the XL was 9% easier through

the water than the next best kayak tank tested and had 18% less resistance than the Wind

Dancer. Because of our extensive research concerning hull resistance our designs take far

more factors effecting drag into account than Sea Kayaker's first simplistic

mathematical model did. Even the computer model Matt now does for Sea Kayaker, that

takes six major factors effecting resistance into account, will overestimate the XL's drag

a little at 4 knots. Most likely because it doesn't model other drag factors we consider

in a design but that haven’t been quantified well enough to make an accurate

prediction of their effect. We invite the skeptical to view the XL's dagger

like hull shape in one of the pictures in the Mariner XL choice in the Sea Kayaks: pickbox

on the sidebar or click on "Mariner XL"

here. |

| You will find

exceptional performance in all our kayaks not just in lessening resistance but in other

aspects like comfort, fit, precise handling, and control in difficult conditions. |

| A Brief Digression |

| A friend of ours and

amateur kayak designer, Dr. Livingston, had just finished his second design as we finished

the Sprite. While his kayak was wider it was tippier. It was also much wetter riding going

with or against the waves than the Sprite. He was disappointed after all the work he had

done and felt the Sprite was the superior kayak. |

| Dr. Livingston had

developed a computer program to design kayaks but he also had a tendency to take things to

the extreme. He designed his first kayak with the help of a computer to absolutely

minimize the wetted surface. It was extremely narrow, extremely round bottomed, extremely

easy to move through the water and as you might have guessed, also extremely tippy.

His paddling friends who paddled Nordkapps (which most paddlers consider somewhat on the

tippy side) labeled it the ‘Death Boat’ and would always let him go first to

check out a rough passage before attempting it themselves. They figured if he could make

it in the ‘Death Boat’ then they could do it too. Dr. Livingston became extremely

good at bracing (and also bought an early Mariner). |

| But, back to the

point. After his frustration with his second more conservative design, his analysis of the

main reason for the Sprite’s superiority was its flare above the waterline, which his

kayak lacked. He soon began to design his next boat, the Ursa Micro, an unusual design

that was extremely flared and extremely short (for a sea kayak at that

time--13’2"). He planned to cut it into three sections and fly it as baggage to

Portugal for a kayak trip so portability was a primary parameter. |

| The Ursa Micro

turned out to be a very interesting kayak. After he had built the first one he joined a

bunch of us for a kayak- surfing/coastal-paddling weekend around Washington’s

northwest tip, Cape Flattery. Two things soon became apparent: the Micro was compatible

with our longer boats for covering miles at cruising speeds, and it was a whole lot more

fun for riding the breakers. Its ability to pivot around quickly because of its short

waterline was a distinct advantage, and its massively buoyant (if odd-looking) flared bow

sections allowed for screaming strait down the face of a breaker without risk of pearling.

Fantastic! No need to throw the boat into a broach and slide in sideways to avoid an end

flip! |

| We considered the

Micro such a fun kayak that we thought about building and marketing Livingston’s

design, but there were a few problems. The molds were not in good shape for production. It

was a very odd looking boat with sort of a camel hump rear deck. Most important, the hull

design was biased toward minimum friction, easy effort cruising. We were really wanting to

maximize the sport/surfing sea kayak concept. We asked Dr. Livingston if he’d mind

our producing a short kayak that would have a bow shape like his "Ursa Micro".

He said he would be flattered and Cam immediately set to work on the design of our

Coaster. |

| Cam drew the plans

once again for his "chine plug" method of construction. Further refining his

plug building technique with this kayak, the Coaster’s original framework was skinned

with 3mm plywood and coated with fiberglass. The deck and hull pieces were then removed

from the frame, glassed on the interior surfaces and seamed together like a typical

production kayak. This gave us a durable lightweight plug that would feel as much like the

finished product as possible while we tested it. The Coaster plug was paddled even more

than our other designs before being put into production, including lots of time in surf. |

| Cam’s friend,

Bill Patterson, was also keenly interested in the project. Bill assisted with much of the

fiberglassing and did a lot of the heavy sweating with the longboard sanding block to fair

the plug after Cam had applied the foam to the plywood and carved the final shape. |

| Afterwards, Cam

(having worked up a good head of steam) also foamed and shaped the XL chine-plug that had

been on the shelf since the previous summer. Then, while Cam was busy preparing the

Coaster plug for production, Matt was fine tuning the XL, adding his keel

‘runner’, shaping the bow, stern and kneebraces, and doing the heavy work with

the longboard preparing it for molding. So we introduced two new designs in 1985. |

| Coaster |

Cam smartly turning the

Coaster with a Duffek stroke |

| The Coaster was

designed to accelerate quickly to help catch and surf waves, not pearl into the trough

once you caught them, rocket across the face rather than mush sideways, be maneuverable

enough to turn back down the wave or completely around before the next breaker hits and

then slip up and over that breaker easily (or punch through bigger ones) so you could get

back out to do it all over again. |

| Cam also wanted it to

have enough speed and rough water capabilities to easily travel many miles up or down the

open coast in search of the ultimate break, rock gardens, channels or sea caves. It needed

to be short and maneuverable for exploring the environment of the open coast. |

| We both loved

paddling the open coast and wanted such a kayak, but back in 1984 the potential demand for

this kind of kayak seemed small to non-existent. So what! Cam wanted one so he built the

Coaster anyway. We didn’t expect it to sell well, because it was built as a labor of

love rather than after a careful study of the potential market. In fact, Cam cared so

little about the market that although the Coaster was a reality in time for the 1985 West

Coast Symposium, he chose to pass up that event and took the only available Coaster to the

Olympic coast for a weekend of surfing and fun, leaving Matt to tell the crowds of

potential customers in Port Townsend that Mariner Kayaks also has another new design

besides the XL, but his selfish little brother has gone of to the coast to play with it so

you can’t see it just yet. |

| Many people have

been led to believe that in hull design "longer is always faster". While this is

true up to a point (if all other things are equal and there is sufficient horsepower to

overcome the extra frictional drag to reach the potential hull speed) it has often been

misinterpreted to mean "longer is easier to paddle" which is usually false. For

instance; the Coaster’s calculated drag at 2 and 3 knots (with 250 pounds aboard--a

load that penalizes smaller kayaks to a greater extent than bigger ones) was less than

almost all of the other 50+ sea kayaks Sea kayaker magazine

previously reviewed. Its

drag was still less than the average at 4 knots (and would most likely be better than

average out to 4.5 knots without the extra 100 pound gear load). Very few paddlers paddle

faster than four knots for any distance even in a kayak without a gear load. When the

Coaster was new we discovered that even when it was heavily loaded it was perfectly

compatible cruising on trips with our longer boats, and whoever was paddling the longer

(supposedly faster) kayak really had to work like a dog just to slowly creep ahead. |

| The Coaster is by no

means a racing kayak but once Cam and I entered a 3 or 4 mile fun race around lake Union

against 20 to 30 other contestants. After the initial sprint I looked back and saw (from

near the front of the pack in my 17 foot Mariner XL) that Cam in his Coaster was near the

back of the pack if not dead last. During the rest of the race he caught and passed all

but me and two others to take 4th place. I was glad the race wasn’t too much longer

because he was closing the gap. My daughter was riding in the back hatch of my kayak,

informing me of his progress, so my claim was that I had a 62 pound weight penalty slowing

me down. |

| The point is that

what is important in a sea kayak is not how fast it can be sprinted a short distance, but

how easily it moves at a good cruising speed. While longer may be faster in a short

sprint, shorter kayaks can often paddle easier at speeds that can be maintained for longer

distances. One of Sea Kayaker’s stronger kayak testers pushed an empty

Coaster for one nautical mile at an average speed of 5.17 knots (almost 6 miles per hour).

More significantly he reported he could maintain 4.9 knots (5.6mph) for long periods. |

| At first, most

paddlers did not know quite what to make of a sea kayak that was only 13’ 5"

long. In an age when most sea kayaks were 16 to 18 feet long it seemed a little odd. But

when paddlers spent some time in the Coaster they often became ardent converts. |

| What really caught

us by surprise was that although the Coaster was designed to have a firm

"whitewater" style fit for people our size (6 foot tall), smaller men and most

women began discovering it was the ideal size and fit for them to use as a touring sea

kayak. In 1985 there wasn’t any competition in the short little 13 to 14 foot sea

kayak segment of the market. Paddlers who had spent most of their paddling life trying to

catch up with their stronger paddling partners in "normal" kayaks discovered

themselves often leading the way when paddling a Coaster. (As well as having more

wetted surface drag from their bigger ‘footprint’ on the water, those paddling

longer kayaks were also often having to drag a rudder along to control the unwieldy

beasts. Towing tank tests have shown that a rudder adds about 10% more drag at 3 knots.

However, no one we know of has ever put a rudder on their small, easy to handle

Coaster.) The word of mouth on the Coaster spread rapidly among smaller paddlers, and

that segment of our market soon surpassed the ‘macho coastal surfer’ segment

that had already made this unique little sea kayak a far bigger success than we had ever

imagined. |

| There are some real

advantages to a small sea kayak. One 190 pound, strong, expert instructor we know credits

his Coaster with possibly saving his life. He was caught by surprise in an extreme

offshore wind that funneled down out of the mountains of Vancouver Island's

Brooks Peninsula one day during a long solo

wilderness trip. He was barely able to turn into the wind and claw his way back to the

protection of the cliffs near shore. He and I had once paddled in winds we measured at a

steady 35 to 40 mph (gusting to 55). He told me the wind that was pushing him offshore was

far stronger than that. He was sure he would not have gotten any other sea kayak to turn

into that wind to even start paddling back to shore. |

| If you’re

willing to accept the few limitations of a relatively small hull, you can have a sea kayak

that will do a lot of things better than any other. The Coaster is much more fun playing

in surf than with touring boats of typical size. It can turn around quickly in sea caves

and narrow channels where most sea kayaks have to back out. It handles beautifully in wind

and waves, moves along easily at cruising speeds and has a surprising amount of volume for

camping gear. And it’s an absolute blast on any kind of wave you can catch, from

tidal rapids and breaking surf to whitecaps, wind waves opposing current, and powerboat

wakes. |

| The Coaster could be

your ideal second boat. Keep your big boat for those long expeditions with the mountains

of gear, and use this one for having fun. The Coaster is also a perfect first kayak. Its

quick maneuverability, responsiveness to the paddle, steady ride and handling ease in

rough conditions make it a great boat for helping novices learn solid paddle technique. It

is not however, a kayak you will ever outgrow. Coasters are paddled by some of the best

open coast paddlers in the world. That’s one in the sea cave on the cover of the June

1997 issue of Sea Kayaker. That’s it again going over the falls on the

cover of the Tsunami Ranger’s "Kayaking Ocean Rock Gardens" video. The

video is also well populated with Coasters in their element. |

| It seems

strange but the little Coaster has more volume (12.45 cu ft.) than the majority of

European sea kayak designs. Also, due to the blunter ends more of the Coaster’s

volume is useful storage space. It took a few years to catch on but for many years now the

Coaster has been our best seller even though many other companies have recently jumped

into the ‘smaller sea kayak’ market. The Coaster received a rave review in Sea

Kayaker magazine’s Summer 1994 issue. Click on Coaster Review here

or COASTER in the "Reviews" pickbox in the sidebar. |

| Mariner II |

A first time paddler tries

out the very first Mariner II at Cape Alava during its maiden voyage down

the Washington Coast (and Matt's photo later became the model for the

Mariner logo Cam drew) |

| The original

Mariner design was a deep, high volume kayak intended for a big cargo capacity. The first

two built were the only two produced unmodified from the original molds. The third one we

started had problems with the gelcoat curing too quickly and we were sure we were going to

have blemished parts. We decided to lay up a particularly lightweight deck and hull if

only to get the gelcoat out of the molds. The parts came out better than we expected but

due to thin areas of gelcoat they were not up to the standards that we would feel good

about selling to a customer. We decided to use the parts to make a second Mariner for

ourselves so we could quit fighting over who got to paddle the first one we built (and who

would be stuck paddling one of our previously purchased kayaks) Actually, we agreed to

take turns but it was frustrating paddling the inferior kayaks and having to wait your

turn for the Mariner. The flawed parts also provided a chance to experiment. Cam decided

to cut 1 1/2" in depth from the midsections to make a lower volume boat with a

snugger cockpit fit. Mating the deck to the cut down hull forced a little more flare in

the midsections resulting in an unexpected increase in stability. The slimmer proportions

and sweeping sheerline of #3 also appealed to Cam’s eye and it became his favorite.

Matt preferred the larger capacity and greater footroom (his feet are size 12) of the

original, so when we made the new plug to build the new ‘vacuum bag’ molds for

the production Mariner we compromised and reduced the depth of the original by 3/4 inch. |

| Testing of the

production Mariner over several years (and a better understanding of the forces involved)

revealed some room for improvements that could enhance its suitability for a wider range

of paddlers and allow it to handle more extreme wind conditions. Some of our friends had

also been expressing a desire for something like a "90% Mariner", so Cam,

remembering his fondness for old Mariner #3, took a stock Mariner hull and cut it down,

increased its flare even more in the forward sections. The result was the Mariner II,

which replaced the Mariner in our kayak line in 1986. |

| In style and

intended purpose the Mariner II is much like the original Mariner. The hull underwater is

classic Mariner, with its fine entry and narrow waterline beam for minimum paddling

resistance. Above the waterline the hull flares out to one inch broader beam with an even

greater flare in the bow sections. This provides noticeably more secondary stability,

enough that paddlers who felt intimidated by the original Mariner are much more at ease in

the Mariner II. A slightly less pronounced keel at the stern along with its shorter length

and lower deck helps kayakers with less skill and power to more easily maneuver a lightly

loaded Mariner II in strong winds. |

| The cockpit size and

arrangement is like the XL, slightly shorter and more pointed in front than the Mariner

and Escape. The medium height foredeck and closer in kneebraces allow even smaller

paddlers to brace themselves solidly in contact with the boat for a more secure cockpit

fit. There is still comfortable roominess for all but the largest bigfoot kayakers (at

least up to size 12). The deep kneebrace molding at the edge of the cockpit extends well

forward providing a secure grip at all positions of the instantly adjustable sliding seat. |

| The Mariner II is

our flagship kayak. It is on our logo and it is our offering to expert and expedition

kayakers. While we don’t sponsor any expeditions, many expedition paddlers have

chosen to use it anyway even though they could have gotten one free or been paid to use a

certain kayak from other companies fleets. Of course the catch is that the sponsoring

company expects you to paddle their kayak on your trip and pretty much obligates you to

say it was great even if you had come to hate it. When someone (like the outer coast long

distance paddlers mentioned earlier) uses a Mariner on their expedition, they paid for it

like anyone else and they are free to say exactly what they think about it. We

wouldn’t have it any other way! |

| Express EX |

Cam Expressing himself |

| By 1989 the

Coaster had become very popular with smaller paddlers and had taken most of the smaller

paddler market from our Sprite. In the intervening years we had really come to like the

Sprite’s size. It was a sporty kayak for paddlers our size but we felt it needed a

longer cockpit like the XL and Mariner II to give medium and larger paddlers like

ourselves easier cockpit ingress and egress. We want to be able to be able to get our feet

into and out of the cockpit while seated in the seat (thereby keeping our center of

gravity low). We could do this in the Sprite, but it was tight and required pulling our

ankles in by hand to get enough bend at the knee. |

| We built a

heavyweight Sprite to serve as the basis for a plug, which Matt then spent considerable

time and sweat cutting up, reshaping, testing and cutting into and reshaping and testing

again and again. Considering the extent of the changes Matt figures it would have been far

easier to start from scratch. It was updated with the features we had found to be most

beneficial in the kayaks we had previously designed.. Matt also added several innovations

he had imagined since our last design, such as, the unique stern that resists pearling

when back surfing and naturally adjusts the tracking stiffness (in the direction most

desirable) considering factors such as kayak speed and gear weight. Then, like the bow,

the stern was also designed to make sliding over kelp easy. While Matt was working on the

plug the Coast Guard was planning to tax all craft over 16’ long (starting at $25 per

year). There was no exemption for ‘human powered’ craft in the plan. The plug

was a few inches over 16 feet. So Matt rounded up the bow a bit to shorten the Express to

just under 16 feet in order to save our customers considerable bucks over the years. At

the same time the paddling and rowing communities were swamping the Coast Guard with

letters about how unfair it would be to exempt a high powered 15’ speedboat and

charge them $25 per year for each of the often several little canoes, kayaks or rowing

shells they owned. They won their exemption from the tax. |

| The hull changes

resulted in increased tracking ability in difficult conditions without reducing the

turning speed and responsiveness people loved about the Sprite. Weathercocking was reduced

to nearly zero and following sea performance was greatly improved. A shorter, higher, and

fuller bow made for a drier ride into head seas and improved on the already great

performance punching out through the surf. These changes also succeeded in giving the new

boat ‘Coaster-like’ performance in resisting pearling when coming in through the

surf. Along with the 2" longer cockpit of the Mariner II Matt added even deeper

built-in knee grips to improve cockpit security while still providing a longer cockpit.

The longer cockpit also allowed more trim adjusting range for our popular sliding seat/

footbrace unit. More ‘V’ in the hulls midsection softened the already soft ride

in head seas even further. The deck was reshaped to increase gear storage, provide room

for bigger feet and make the cockpit even less likely to be washed by a wave. |

| We got the first Express

EX finished just in time to introduce it at the Sea Kayaking Symposium at Port Townsend in

1990. It was a smash hit. Paddlers loved the combination of effortless tracking and the

quick response to a lean. And the precise carved turns where the angle of lean controls

the tightness of the turn. Smaller paddlers also loved the sporty handling in such a high

volume kayak but several also wished it fit them a little tighter at the kneebraces. |

| After the symposium Matt

headed directly out to the Washington Coast to try out the final product in the surf. He

tells it this way: |

| "Going out the bow

pops up quickly to ride over the waves and soups thereby keeping most of the in rushing

breakers from slugging you in the chest and stopping your progress. Surfing in on a wave

the hardened chines bite into the wave face and let you surf across it at high speed

(rather than just mush in sideways as with most kayaks it acts more like a surfboard). You

can still slide in mostly sideways if you prefer by bracing further forward with your

paddle or moving the sliding seat further forward. |

| "Once the wave had

broken and after the initial ‘Maytagging’ the Express EX would slide sideways

smoothly with the bow slightly forward, but unlike most sea kayaks the bow did not

repeatedly snag in the green water in front of the wave only to be bounced forward by the

broken wave again and again. While skidding sideways it was easy to brace further towards

the stern pivoting the bow forward in order to hit the beach coming straight in or back

off the soup. |

| "The Express

rivaled the Coaster in its ability to come straight in through the surf without pearling

the bow and end flipping. I was trying hard to do an ender in the Express EX. Although

several times I had it standing nearly vertical in six foot dumping breakers each time I

either rode straight down the wave and out in front of it or if I was unable to keep it

pointed straight as the breaker hit the tumbling water quickly swung my stern around into

a sideways skid (like most other kayaks must adopt early in order to prevent an ender).

The closest I came to pearling the bow was when I leaned well forward in an attempt to

force the bow under. About 1" of water ran up the nearly vertical deck before the bow

again broke the surface and surfed off straight in front of the wave. |

| "Even more

amazing, when I was unable to punch out through a bigger breaker, instead of the usual

rear flip that ensues the Express EX surfed backwards long enough without pearling to give

me time to get turned off to the side. I found it great fun to surf backwards on three to

four foot breakers. The stern didn’t pearl even when the waves broke into soup. I did

discover that when turning to one side while back surfing one must be careful not to lean

the Express away from the wave (a technique to turn quicker). If you do this the side

pressure against the pronounced stern keel can become too much to overcome with knee

pressure, eventually forcing a capsize down the wave. |

| "A little later

I looked back to see the biggest swell of the day over my shoulder. I was determined to

ride this one straight in and do everything I could to end flip the Express as it broke. I

was having an incredible ride and as the wave steepened to break I leaned forward and

waited for the bow to pearl to let the breaking crest take my stern over the top. The

lifting planes I had designed into the bow’s shape foiled my plans for an endo. At

the speed I was traveling they kept the bow planing on the surface. The only sure

indication that the wave had broken behind me was that some spray was thrown over my head

and shoulders as I surfed along in front of it. |

| "I was overjoyed

by the whole experience in the surf, our design concepts worked even better than I had

hoped. As I used it more and tested its capabilities I found myself wanting to paddle it

more. It was so much fun carving turn sometimes I would do it just for kicks even though I

had no need to turn." |

| The original Express

was a deep boat with lots of gear volume and foot room for large paddlers. To better fit

the small to average sized paddlers we added 1/2" to the kneebrace pads. This helped

some, but to better serve those paddlers who would most benefit from this smaller hull we

soon decided to make another version. Cam was able to fairly quickly get a new model ready

for production by simply removing almost an inch from the hull of the EX and joining the

existing deck. The result we dubbed the Express LP at first, but as it became the far more

popular version we labeled the original higher volume Express the Express EX (expedition)

and called the new LP simply the Express. |

| Express |

| We made the Express

(LP) in 1991 by cutting 7/8" from the EX hull. Because only the hull was cut down the

flared hull needed to flare out at a greater angle to meet the (same but now lower) deck.

This gives the Express a slightly more stable feel than the EX because the increased flare

angle brings the substantial secondary stability into play at less of an angle. That is

about the only noticeable performance change from the EX (besides the eight gallons less

total volume, the comfortable shoe size limit reduced from size 14 to size 12, and less

total windage). |

| The Express has

become Matt’s favorite kayak to paddle on day trips, especially into areas where

maneuverability will be desirable such as snaking up narrow estuaries. In fact when

paddling the Express he will purposely paddle into tight areas because it is so much fun

to wiggle out of them again with the Express’s precision handling. |

| The Express is

especially maneuverable at the bow. It responds immediately to bow rudder strokes like the

‘Duffek’ and ‘Cross Bow Draw’. Go to "PADDLING" in the

"Manuals:" pickbox on the sidebar and go to the ‘Turning Strokes’

section or click "Bow Rudder Strokes" here

for a direct link to a description of these strokes. Use them to pull the bow around tight

corners in narrow twisting channels. The stern carves around and follows the bow without

skidding over into the outside bank (as happens with most highly maneuverable kayaks).

It’s almost magical. You’ll love it like the reviewers of the Elan (same hull as

the Express) did in Sea Kayaker's April 1999 review. Click "Elan reviewer's comments" here or

go to "ELAN" in the "Reviews:" pickbox on the sidebar for the full

review. |

| Mariner MAX |

Cam in the Mariner MAX |

| The next

refinement in our stable of kayaks happened in 1992 when Matt decided to do some reshaping

on the venerable Mariner XL. He relates this story of how the Max came to be: |

| "In the Spring

of 1991 I took a trip to Baja. I wanted to photograph our new Express (EX) so I lent it to

George Gronseth to use on the trip and chose to use our Mariner XL. I chose it because it

was the most stable kayak in our current stable. I hadn’t used it on a big trip in a

few years. I had been paddling most longer trips with my friend Bruce who I had raced with

in recreational kayak races in past years. Bruce has an original Mariner, a wing paddle,

was still in training and has only two speeds: ‘fast’ and ‘stopped’. I

needed as fast a kayak as possible to keep up. Our fastest current model was the Mariner

II. But, I digress. My point was that I fell in love with the Mariner XL all over again on

that Baja trip. It just did everything I asked of it extremely well. But I was torn, I

also loved the nimble handling of the Express. Would it be possible to have it all in one

kayak. I realized that with the concepts that had proven themselves in the Express we

could make the XL (Sea Kayaker’s ‘Hot-rod’) into an even sportier

handling kayak without losing any of the great tracking ability of the loaded XL in rough

conditions and following seas. With the changes Matt made to the XL that became the

Mariner MAX we: 1) improved on the already amazingly dry ride; 2) retained the incredible

following sea and wave surfing performance; 3) made the kayak more sporty and maneuverable

as well as, 4) able to turn into higher winds in the bargain. |

| "The MAX

can do it all from surfing breakers to snaking up twisting channels. High seas and howling

winds empty to month long unsupported camping trips. And it does it all with aplomb and

without a rudder. The Max is the most neutral kayak we have ever used. It stays level in

steep waves (others have described it as gyroscopic). It stays easily on course at any

angle to the wind and waves. Neutral handling means you don’t have to fight a boats

"tendencies" all the time. A neutral kayak puts a capable paddler firmly in

control. But hey, don’t believe us, read what Sea kayaker magazine’s

expert testers had to say in their Dec. 1995 issue’s review." Click on MAX reviewer's comments here or for the review from the beginning open the

"Reviews:" menu in the sidebar and choose "MARINER MAX" . |

| ELAN

|

| A few of the shorter

waisted Express owners (who we happen to paddle with quite frequently) were telling us how

much they loved their boats but if they could change one thing they would lower the

cockpit so they had more elbow clearance like they had in the Coaster. Not having short

waists ourselves we had never seen this as a problem in our kayaks but we could relate

because of our experiences with some of the very deep kayaks that we have test paddled. |

| Besides lowering the

cockpit, what else could we change about the Express that would suit these paddlers even

better? Well a smaller or shorter waisted paddler is a more stable paddler and could

benefit in several ways by having a narrower less stable kayak. It would be easier to

paddle due to less drag and wave making. It would be easier to reach over the deck to take

paddle strokes (Note: all our kayaks are already narrower in the area where the stroke

begins and we keep the area in front of the cockpit low and fittings in this area recessed

for paddling comfort as well). A narrower kayak will be easier for a small paddler to

lean--especially when carrying a gear load. We wouldn’t want to deprive our small

customers of the fun and control that results from steering their kayak with their entire

body. (It’s just so much more satisfying than diddling your toes to control that

puppet behind your back that pushes your back end off to one side or the other. What a

drag, even more so when steep criss-crossing waves are hitting the puppets sides, and

thereby jerking your hind end back and forth.) |

| Of course with a

lower deck the smaller paddler will have to give up some gear room (but with

its full ends it still has more gear capacity and total volume than most

British expedition kayaks). Cam removed

about 2 inches from our Express EX (the tippier of the Express hulls), 1 1/4" from

the hull and the rest from the deck. This made the Elan about 1" lower and 3/4"

narrower than the Express LP’s our short waisted friends already owned. That would

give a smaller paddler much better elbow clearance but also lower the sidewind profile so

a smaller paddler could handle it better in higher winds. Just for good measure Cam

lowered the rear of the cockpit another inch by recessing the back of the

cockpit coaming somewhat into the back deck.

The result is nearly 2" more elbow clearance than with the Express. With no

Coast Guard tax on kayaks over 16' to be concerned with that year, Cam added about 2" to the tip of the bow making it more pointed again like on the MAX. We

received a rush of orders for the new Elan as soon as it was completed because the kayak

grapevine was hard at work and we had satisfied a small niche in the market where there

apparently was a good deal of pent-up demand. If you are small or short waisted and want a kayak

that really fits you (in many more ways than just in the cockpit) be sure to try our Elan.

Of course there have been some guys weighing up to 160 pounds who found the firmer fit and

narrower kayak (21.5" beam) to be just what they wanted and have purchased Elans as

well. |

| So far this

success has been almost entirely by word of mouth since we have never advertised the Elan

(until now), made a brochure (or even a name decal) for it, or sent announcements out to the media. If we

don’t have a picture of one yet here we can tell you it looks a lot like a scaled

down Mariner MAX. Later

note: Sea Kayaker magazine testers reviewed it in their

April 99 issue, click Elan Review

here or on ELAN in the "Reviews:" pickbox in the sidebar to read what they had

to say about it. Sea Kayaker allowed us to use their top and profile

pictures from that review here. ©1999

Matt and Cam Broze

Mariner Kayaks |